Rust - A multi-paradigm language

What makes programming languages feel the way they do?

1 algorithm - 3 programs

What makes these programs different?

Different ways of thinking

- Like in the real world: Bureaucracy vs. companies vs. associations

- Different organization principles to achieve similar goals

Different requirements

- Hardware is inherently imperative:

- “Do this, then this, then this” (machine code instructions)

- “But at the same time also do this and this” (parallelism)

- Data is often more functional: Collections, streams, transformations

- Many problems share some characteristics, so we want to allow code reuse

- Familiarity helps with learning a language, so we want familiar syntax

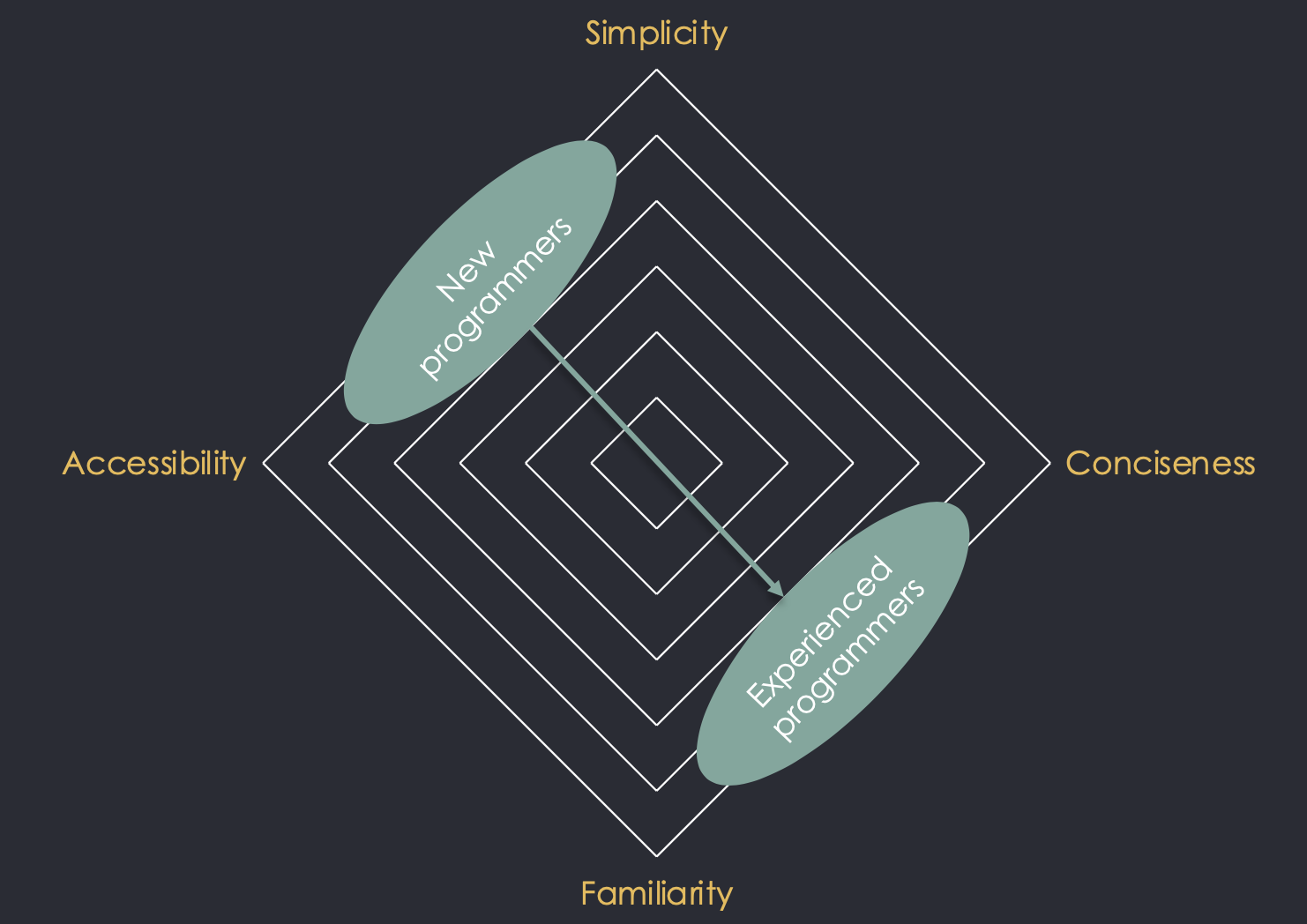

Usability of programming languages

Simplicity: How many concepts to memorize?

Conciseness: How much code to write to solve a problem?

Familiarity: How many well-known concepts and syntactic elements?

Accessibility: How easy to install, build, run?

Usability of programming languages

Some are mutually exclusive!

Programming paradigms

- The answer to the question: What are good abstractions for computation?

- Useful patterns that emerged over decades of research and usage

- Instead of reinventing the wheel, new languages can use these patterns in their design

The most important programming paradigms

- There are dozens of programming paradigms in use today

- [Van Roy 2009] gives a good scientific introduction

- We will focus on these five:

- Imperative programming

- Object-oriented programming

- Functional programming

- Generic programming

- Concurrent programming

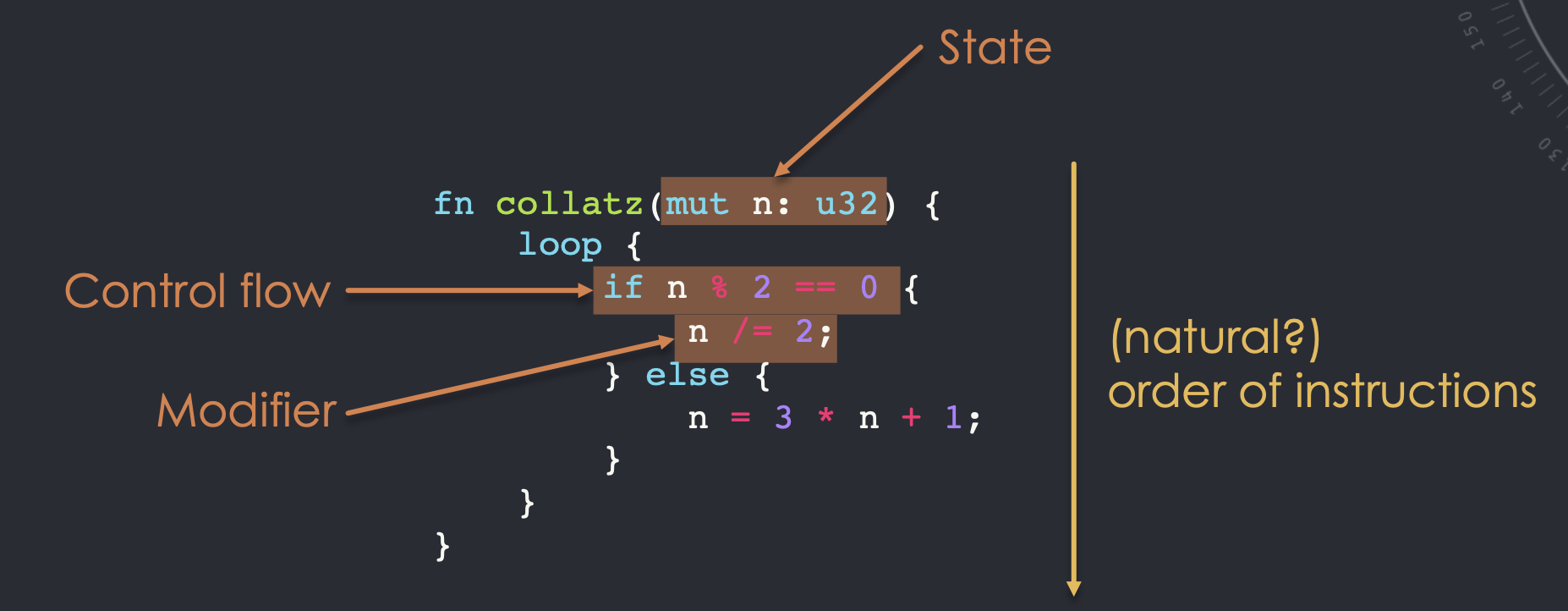

Imperative programming

- Statements modify state and express control flow

- Defining how a program should achieve a result

- (Is there any other way? Stay tuned!)

- One of the oldest paradigms: CPUs (and Turing Machines) are imperative in nature

Object-oriented programming

class Cat {

std::string _name;

bool _is_angry;

public:

Cat(std::string name, bool is_angry) : _name(std::move(name)), _is_angry(is_angry) {}

void pet() const {

std::cout << "Petting the cat " << _name << std::endl;

if(_is_angry) {

std::cout << "*hiss* How dare you touch me?" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "*purr* This is... acceptable." << std::endl;

}

}

};

int main() {

Cat cat1{"Milo", false};

Cat cat2{"Jack", true};

cat1.pet();

cat2.pet();

}Object-oriented programming

class Cat {

std::string _name;

bool _is_angry;

public:

Cat(std::string name, bool is_angry) : _name(std::move(name)), _is_angry(is_angry) {}

void pet() const {

std::cout << "Petting the cat " << _name << std::endl;

if(_is_angry) {

std::cout << "*hiss* How dare you touch me?" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "*purr* This is... acceptable." << std::endl;

}

}

};

int main() {

Cat cat1{"Milo", false};

Cat cat2{"Jack", true};

cat1.pet();

cat2.pet();

}- Combine state

Object-oriented programming

class Cat {

std::string _name;

bool _is_angry;

public:

Cat(std::string name, bool is_angry) : _name(std::move(name)), _is_angry(is_angry) {}

void pet() const {

std::cout << "Petting the cat " << _name << std::endl;

if(_is_angry) {

std::cout << "*hiss* How dare you touch me?" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "*purr* This is... acceptable." << std::endl;

}

}

};

int main() {

Cat cat1{"Milo", false};

Cat cat2{"Jack", true};

cat1.pet();

cat2.pet();

}- Combine state and functions

Object-oriented programming

class Cat {

std::string _name;

bool _is_angry;

public:

Cat(std::string name, bool is_angry) : _name(std::move(name)), _is_angry(is_angry) {}

void pet() const {

std::cout << "Petting the cat " << _name << std::endl;

if(_is_angry) {

std::cout << "*hiss* How dare you touch me?" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "*purr* This is... acceptable." << std::endl;

}

}

};

int main() {

Cat cat1{"Milo", false};

Cat cat2{"Jack", true};

cat1.pet();

cat2.pet();

}- Combine state and functions into functional units called objects

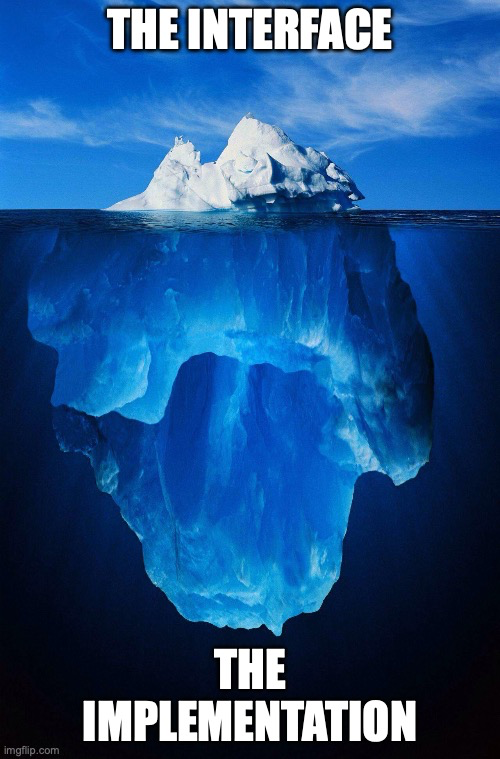

Object-oriented programming (cont.)

- OOP builds on information hiding

- Interaction through well-defined sets of functions (the interface)

- Doesn’t translate well onto hardware

- OOP on multi-core CPUs is very difficult

Functional programming

- Solve problems through the application and composition of functions

Functional programming

- Introduces higher-order functions: Functions taking functions as arguments

Functional programming

- Great for writing concurrent code

struct Student {

pub id: String,

pub gpa: f64,

pub courses: Vec<String>,

}

fn which_courses_are_easy(students: &[Student]) -> HashSet<String> {

students

.par_iter() // Run on all CPU cores (using the rayon crate)

.filter(|student| student.gpa >= 3.0)

.flat_map(|student| student.courses.clone())

.collect()

}Generic programming

Generic programming

- Write code once in a generic way

Generic programming

- Write code once in a generic way, then instantiate using specific types

Generic programming (cont.)

- Many ways of realizing generic programming:

- Subtyping (e.g.

virtualfunctions) - Parametric polymorphism (e.g.

max<T>) - Ad-hoc polymorphism (e.g. operator overloading)

- Subtyping (e.g.

- Some can be realized purely at compile-time, resulting in no runtime-overhead

Concurrent programming

- Write code that does multiple things within the same time period

- Weaker form of parallelism: Multiple things happening at the same time

- Example from the

tokioRust framework using async / .await:

use mini_redis::{client, Result};

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Open a connection to the mini-redis address.

let mut client = client::connect("127.0.0.1:6379").await?;

// Set the key "hello" with value "world"

client.set("hello", "world".into()).await?;

// Get key "hello"

let result = client.get("hello").await?;

println!("got value from the server; result={:?}", result);

Ok(())

}Multi-paradigm languages

- Most paradigms are not mutually exclusive and offer useful features

- Most modern languages are multi-paradigm languages

- Rust is imperative, functional, generic, concurrent

- But not object-oriented!

- No

class, no inheritance

1 algorithm - 3 programs (recap)

Identify the programming paradigms that these three snippets use

Programming paradigms are ways of thinking. Which one fits your mind best, which one will stretch it the most?